About John

|

John was born in Boston to restless parents who relocated frequently during his childhood and adolescence. He is happy to find himself back in New England, but values the significant portion of his upbringing spent in the Midwest. Formal milestones in John’s personal and professional development include a BA from Hamilton College, and advanced degrees in architecture from the University of Pennsylvania (where one day he spent several minutes in the same studio as Louis Kahn) and in real estate from MIT. He is a registered architect in Massachusetts.

In his first previous life he was employed by architecture firms and concentrated on large scale commercial and infrastructure projects. In his second previous life he worked in corporate real estate. It was during this period that he became an autodidact demographer, developing analytic techniques to assist large corporations with their global site selection and real estate portfolio optimization strategies. Convinced that there must be something more he could do, but not sure exactly what, John has entered a still evolving third phase. He currently apportions his time among providing care and companionship to various family members, some of whom are not human; managing the inanimate aspects of his household including buildings, grounds, equipment, rolling stock, general ledger, and chip containing devices; and performing liaison with federal, state and local governments. Like many in his age cohort, John has a bucket list. His includes activities aimed at putting him in closer contact with the joys of unfamiliar places, foreign languages, art and design, science, mathematics and history. Some of these interests animate the work shown in this website. |

About the Work

|

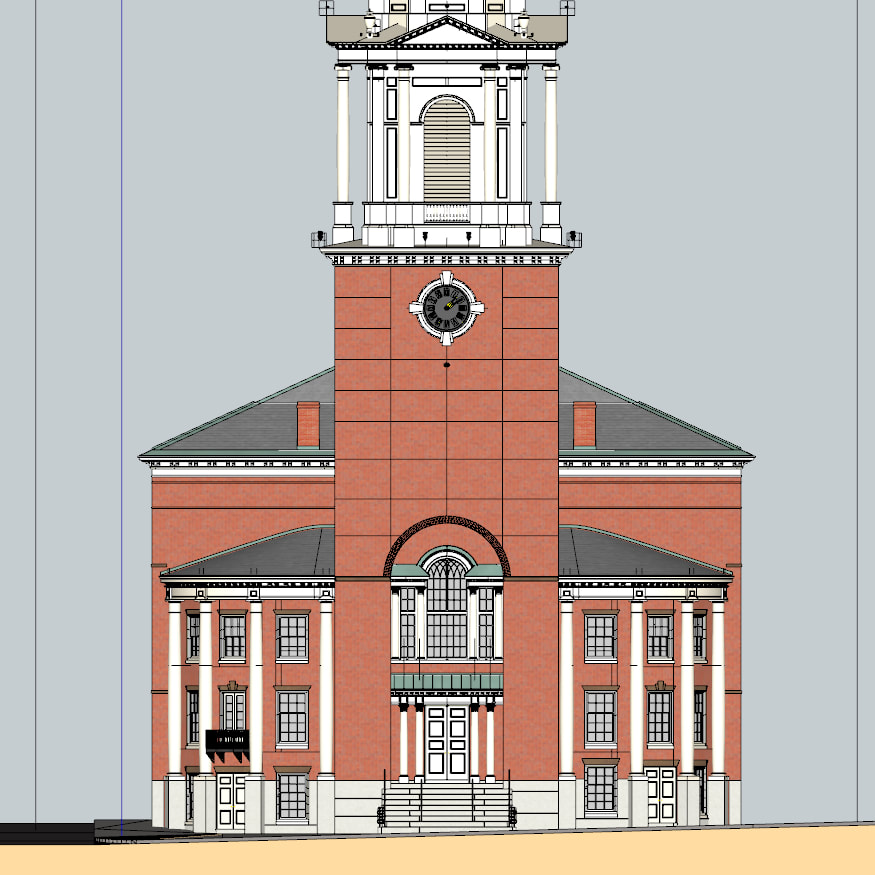

Nearly all the work I present in this website is produced digitally, utilizing several software packages. Except in the most limited of circumstances (explained later) there is no photographic content of any kind. Almost all of the subjects depicted are architectural, though that definition is stretched in a few instances. The majority of images represent buildings or objects that exist in the world and can be visited, but a few are entirely imagined. The images of actual buildings can be thought of as architectural portraits. Like any good portrait they are meant to add something to the observer’s appreciation of the subject, deeper insight perhaps, or a new revelation. For discussion purposes the images are probably best described as renderings.

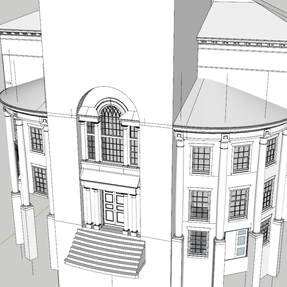

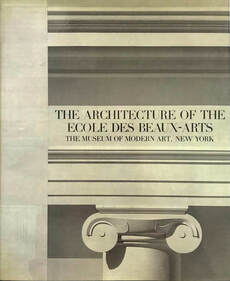

The renderings differ from photographs in significant ways, but no comparative value is assigned; neither is categorically better than the other. In capturing architectural subjects, renderings offer the possibility to depart from actual conditions across multiple dimensions. Virtual repairs to deteriorated building parts can be made. Inappropriate additions can be removed and missing original features restored. Obscuring (cars, vegetation, people) and infelicitous (drainpipes, air conditioners, awnings) objects can be removed. Critical decisions about what to highlight and what to de-emphasize are fully enabled. Color schemes can be refined, altered or transformed outright. While it is true that many of these modifications are possible with fully featured processing software, somehow this seems antithetical to the photographic spirit of recognizing and capturing the elusive “best shot.” Rendering, as practiced in the work in this website, is more akin to a patient process of design and elaboration than to seizing the moment with a camera. The majority of the renderings on the site are directly projected elevations of their subject buildings, views not available to photographers. Elevations endow their subject with a powerful presence, a sense of dignity and groundedness. They enable the viewer to accurately assess the proportions of the subject, and thus can be considered a form of reverse engineering providing insight into the designer’s original intent. Of course, in the real-world buildings are experienced in perspective, and good designers anticipate the way elements of their buildings will be perceived from various vantage points. This suggests that toggling back and forth between perspective and elevation views might be an ideal way to understand and appreciate the architecture. With existing subjects, I begin with field reconnaissance consisting of taking reference photographs and obtaining certain critical measurements. Over time it has become apparent that very few of the latter are actually required, as it is possible, in fact desirable, to infer the rest from careful eyeballing of building proportions. One helpful truth about most buildings is that they are at a fundamental level stacks of some repeated module – bricks, stones, clapboards, metal panels, etc. – so that assessing the height of a structure is often just a matter of counting. Sophisticated (and expensive!) laser-based systems for recording existing building conditions, sometimes mounted on drones, exist and produce extraordinarily accurate results, but these are not available to me, as much fun as I think it might be to be a drone pilot! With the research in hand the next step is to draw the subject in three dimensions on the computer with modeling software. This is a painstaking process and one which consumes the bulk of the time - usually a few weeks - required to produce an image. If the subject has the occasional exceptionally complex plastic shape – a cartouche, a sculpture in a niche, a Corinthian capital – I will sometimes use photogrammetry software to capture it and blend it as best I can with the main building model. I have to concede that there is an upper limit to the sculptural richness I can model, so, for example, Baroque and Art Nouveau buildings are probably not going to show up in my work. Advantage photography! During the modeling phase I take care to render the subject as accurately as possible. In the early going, proportion, completeness and what I might call documentary discipline rule the day. Many of the renderings could in fact be used in line with the intent of the measured drawings created for the federal program HABS, in that it would be possible to rebuild from them in the event of a catastrophic event like a fire. In most cases even the smallest details in my work, like brick coursing, muntin patterns, and shingle counts, are dependably accurate. But because the ultimate objective is to produce pleasing, compelling and provocative images, a time comes when the documentary approach needs to cede to the dictates of the picture. As noted, some things are left out or simplified because they don’t contribute to, or even obscure, the desired effect. At some point a reckoning of where to place the subject relative to the assumed observer and within the boundary of the picture plane must be made. Critical decisions about whether to provide the subject with an entourage and what it should be are necessary. Questions of establishing a visual hierarchy of features, regulating shade and shadow (which means establishing time of day and season, sun position and interior lighting, if applicable), and working out the color palette must all be addressed. Assigning textures (think materials like brick and granite) to surfaces is an absolutely critical yet nuanced step at this stage of the process. This is where photographic elements do sometimes get introduced. The building model itself is a 3D digital construct, but in some cases the model surfaces are “painted” with material proxies derived from photographs. All these considerations of composition and refinement dominate the latter stages of the modeling phase and are independent of pure description. When the model is complete the next step is to render it, which is accomplished with software distinct from but compatible with the modeling program. At its essence this software governs the play of light on the model. In crude terms it bounces light off the model in multiple successive iterations until a convincing rendering is achieved. This process can take a few hours and is aptly likened to cooking something in the oven – you can walk away while it’s going on but want to check periodically for “doneness.” After rendering the model, a final processing step is usually necessary. I attempt to achieve as much of the desired final effect as I can without it but have come to the conclusion that a rigorously pure approach to the work, that is one that excludes post processing, is too limiting. This final step uses graphics editing software which enables a range of enhancements to the renderings including the introduction of text and title blocks, the layering in of backgrounds such as sky treatments, and subtle qualitative effects which determine how the rendering is perceived. In the latter category, editing tools which permit me to move away from the hyper realism inherent in the rendering program to “add back” visual noise, texture, and some imprecision of line, are vitally important. An aspirational example for what I am trying to achieve with the work exists. Unfortunately, as a goal it is painfully out of reach for the skills and methods at my disposal but serves as lodestar. This is the work of the students and faculty in architecture at the Ecole des Beaux Arts during the 19th and early twentieth century as presented to great effect in a landmark exhibition at MOMA in the late 1970s. It inspires me still. If you have access to the exhibit catalogue, or better yet a chance to see the works themselves, there you will find elaborate elevations of fine buildings, most often rendered seductively in watercolor, which dependably deliver the twin mandates of description and delight. |